John Deere

Reality Check for Sustainable Farming

Situation

When deciding how to prepare their land for the next season, growers traditionally collect data from their harvest yields and through soil and plant samples. The analysis is rudimentary and spotty at best, with data points few and scattered unevenly. This leads to blanket-treatment in a “better-safe-than-sorry” fashion: If there is signs of fungus growth in one part of the field, farmers will treat the entire plot. If growth stagnates in some patches, fertiliser will be applied everywhere. The result is unnecessary use of precious resources and continued soil degradation.

Precision farming is based on high resolution maps that overlay multiple data sources from sensors in the sky or on ground based equipment. Combines collect information where there is more or less grain to be harvested, satellite imagery will provide information on nutrition, soil sensors can collect information on minerals and water and much more. GPS-controlled machinery will use this information to apply just the right amount of treatment at exactly the right spot. So goes the theory.

Task

John Deere partnered with BCGDV to investigate which part of this technology was most valuable to farmers. As corporate partners, they aimed to develop adjacent, digital business models that would in turn aid market penetration for the next generation of farming equipment.

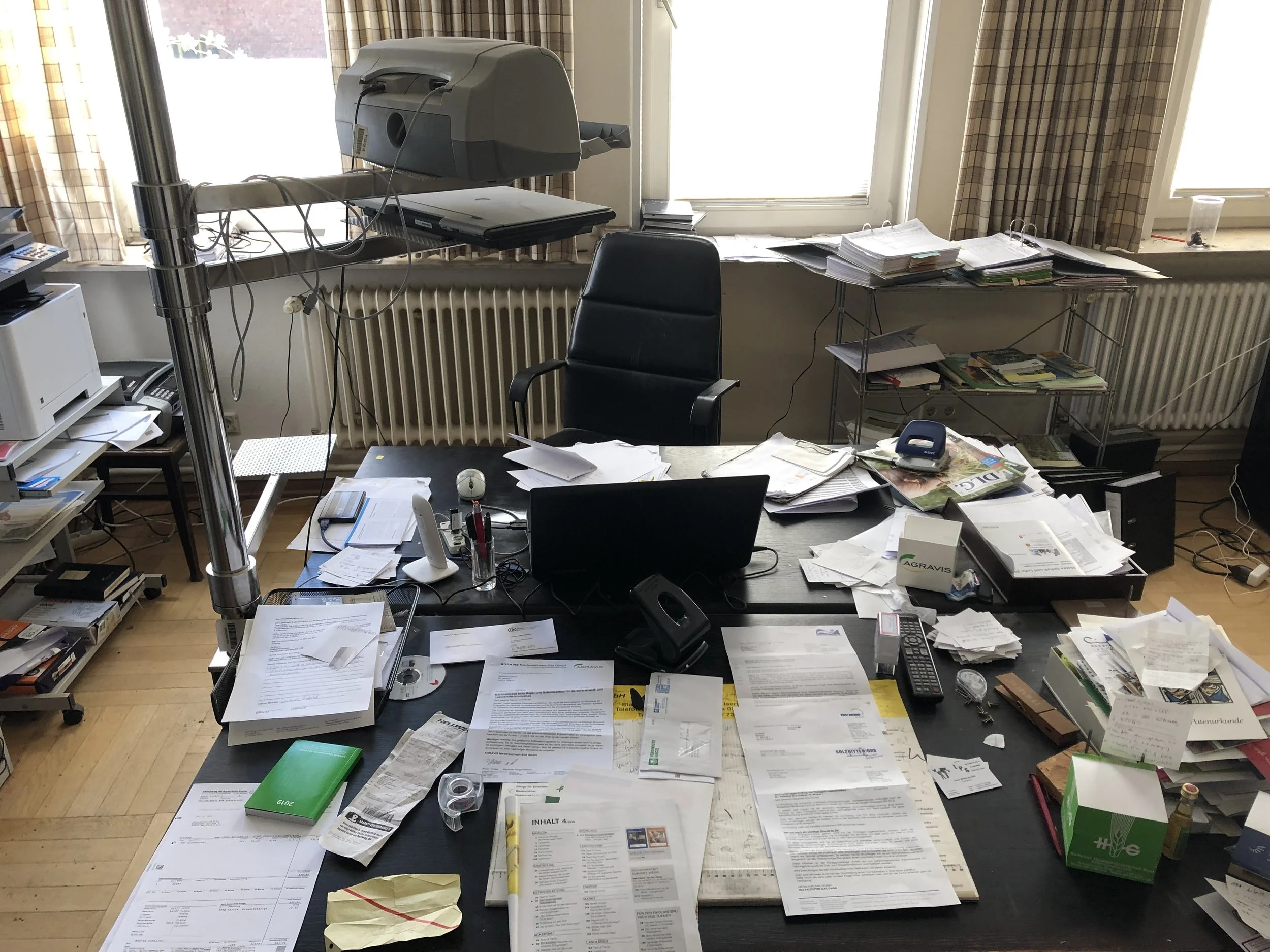

Riding along with farmers to observe interaction patterns

Yield maps in use on a 1.000ha+ farm in Ukraine

Action

I led ethnographic research in three European countries to validate a wide range of hypotheses around adoption and deployment of novel precision farming solutions.

We met farmers on the ground to understand how they looked at investments into technology and what digital adoption meant in their day-to-day lives. This meant spending time on tractors, in sheds, on paddocks and in offices in the Donbas region, in Lower Saxony, Baden-Württemberg and Bourgogne.

Result

We learned that farmers felt inundated by information about ever more solutions aimed at them and purportedly making their lives easier and their bounties bigger. They described a landscape of technological choices that were almost impossible to make, due to a lack of solid, practical experience in their peer groups. It seemed almost like they were challenged to a culture war and many felt the urge to resist, worried they were the target of large corporations and their business interests. The synthesis of these findings led to an entirely new proposition by our team: The creation of learning centers, ideally with a mission that was decoupled from selling any particular solution. It wasn’t a technological problem farmers were facing, but a trust and knowledge problem. They needed advisors by their side to help them keep apace with innovation, enabling them to make prudent judgment calls about where to deploy their capital.